Plant hormones-Abscisins

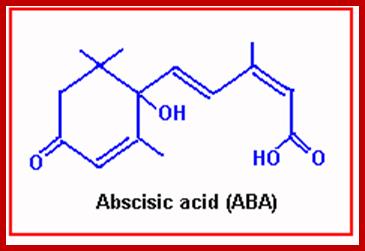

Plant physiologists knew presence of growth inhibiting compounds in plants for sometime. But the active substance responsible for it was discovered by Ohkuma and Cornforth, later Ohkuma established its structure in 1965; Cornforth further confirmed this in the same year by synthesizing the compound in the laboratory. Today, we know that growth inhibiting substance as Abscisic acid or Abscissin II, which was once called as ‘Dormin’. Besides ABA, plants also contain other natural growth inhibitors such as Coumerin, Ferulic acid, Para ascorbic acid, Phaseic acid, Violoxanthin and others. In addition, plant chemists have identified some synthetic growth inhibitors. Ex. 2,3,5 tri iodo-benzoic acid, morphactins, caproic acid, phenyl propionic acid, Malic hydrazide, etc.

www.users.rcn.com

Distribution:

Abscissin has been isolated from a wide variety of plants. The amount of ABA found in plants varies from species to species and from organ to organ. For example, in the pulp of avocado fruits the concentration of ABA is 10 mg/kg. And in the dormant buds of cocklebur it is 20 mg/kg. Again depending upon the environmental conditions the concentration of ABA varies in the same part or the organ of the plant body. In the leaves of phaseolus vulgaris, if the plant is subjected to water stress within 90 minutes the amount of ABA concentration raises from 15 mg/kg to 175 mg/kg. Intense light and other dormancy inducing factors are highly effective in increasing the concentration of ABA is the plant body.

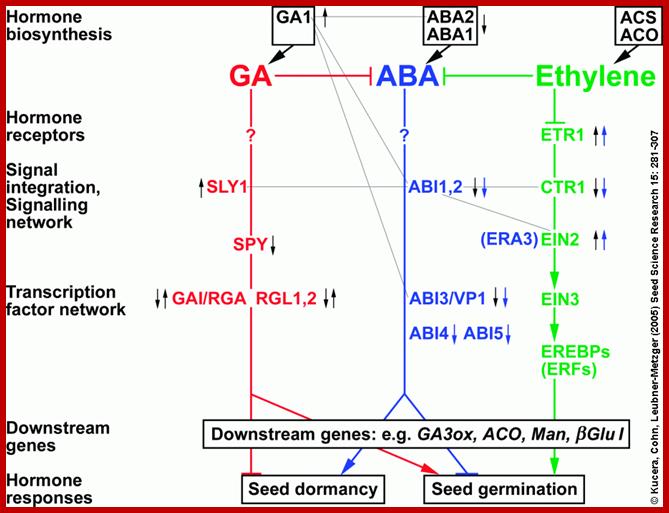

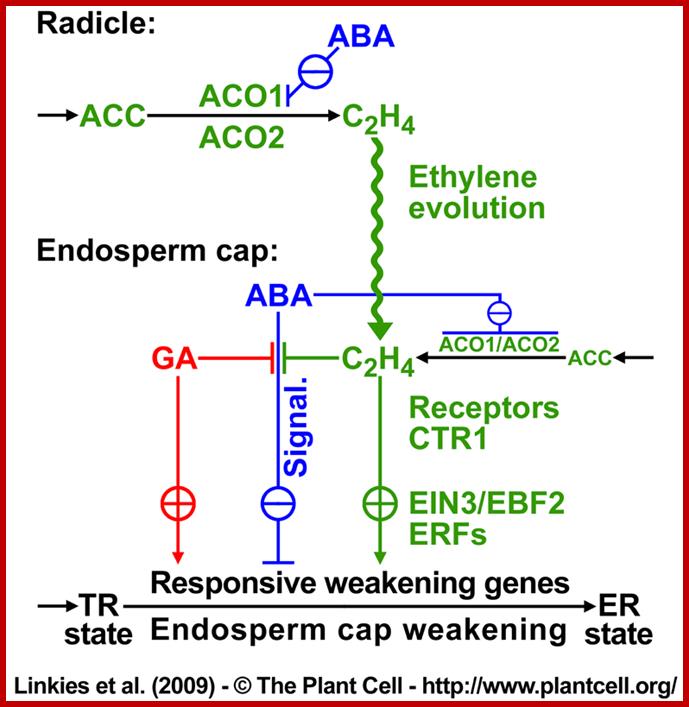

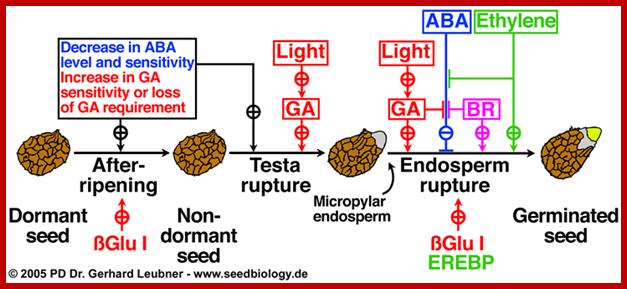

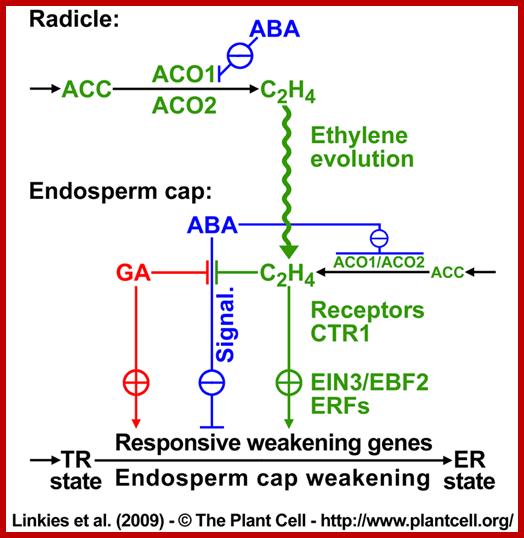

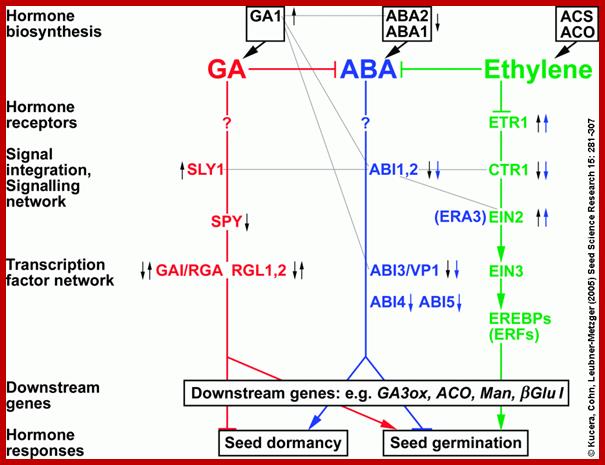

Schematic interaction between ABA and GA and Ethylene signaling pathway in regulating seed dormancy and germination; http://www.seedbiology.de/

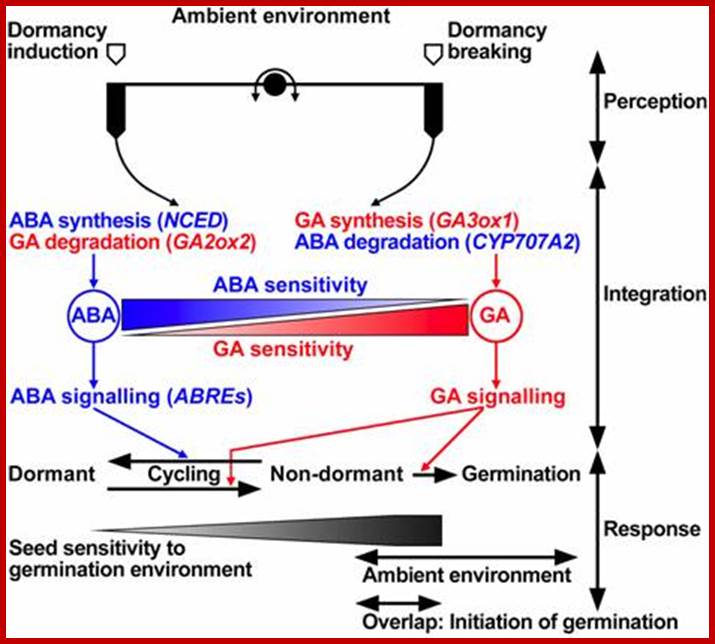

GA and ABA counteraction; www2.warwick.ac.uk

Proposed model for hormonal regulation of endosperm cap weakening and rupture; linkies et al 2009; www.seedbiology.de

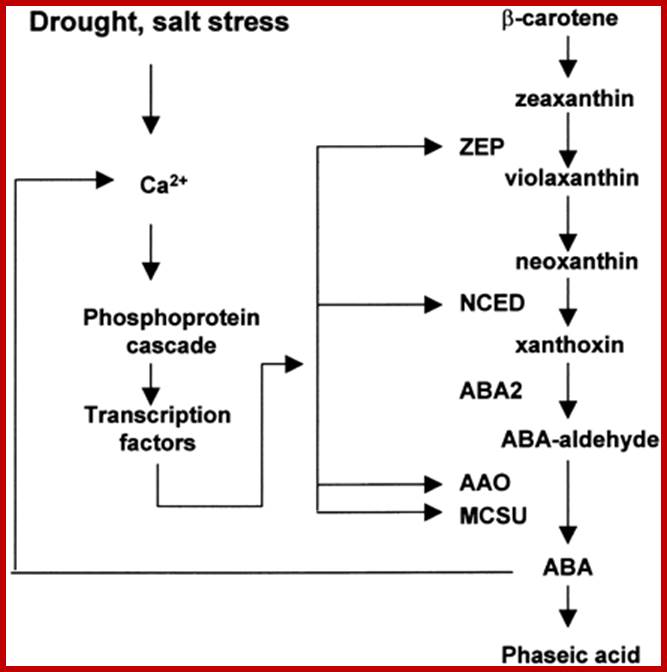

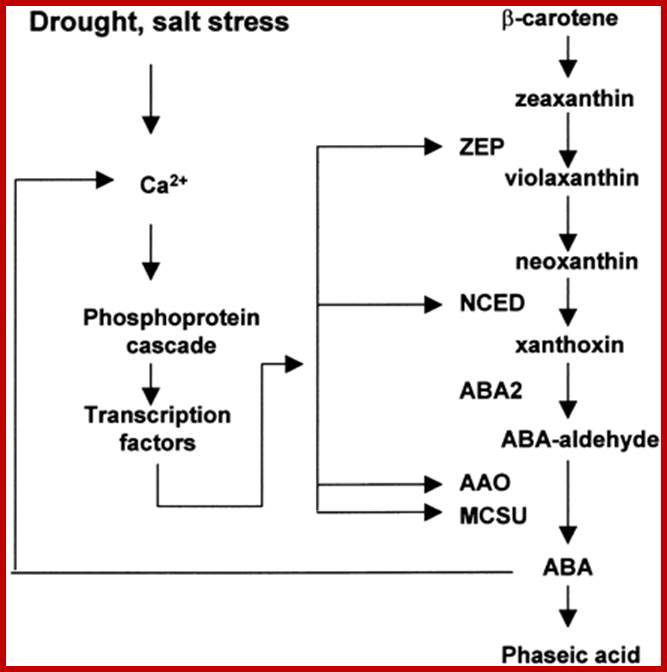

Pathway and Regulation of ABA Biosynthesis.

ABA is synthesized from a C40 precursor β-carotene via the oxidative cleavage of neoxanthin and a two-step conversion of xanthoxin to ABA via ABA-aldehyde. Environmental stress such as drought, salt and, to a lesser extent, cold stimulates the biosynthesis and accumulation of ABA by activating genes coding for ABA biosynthetic enzymes. Stress activation of ABA biosynthetic genes is probably mediated by a Ca2+-dependent phosphorelay cascade, as shown at left. In addition, ABA can feedback stimulate the expression of ABA biosynthetic genes, also likely through a Ca2+-dependent phosphoprotein cascade (Xiong et al., 2001a, 2002; L. Xiong and J.K. Zhu, unpublished data). Also indicated is the breakdown of ABA to phaseic acid. AAO, ABA-aldehyde oxidase; MCSU, molybdenum cofactor sulfurase; NCED, 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase; ZEP, zeaxanthin epoxidase.

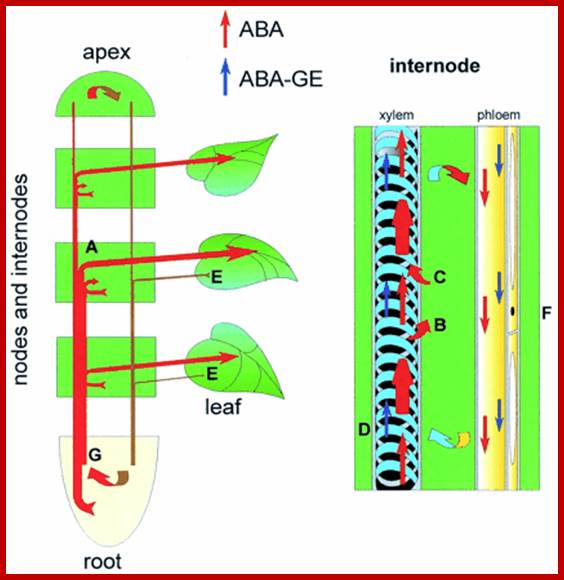

ABA like other phytohormones exists in free-state or in bound form. The free state of ABA is supposed to be an active form. The bound forms of ABA are conjugates of glucose and its derivatives. During flowering it can also binds to FCA a flowering factor and delays flowering. Depending upon the influencing factors, they undergo rapid changes from one form to another to elicit their respective functions. ABA is mostly transported through sieve tubes in the plant body. But the rate of transportation ranges from 25-45 cm/hr, which is far below the rate of sucrose transport that takes place in sieve tubes, which suggests that ABA’s transport is independent of sucrose.

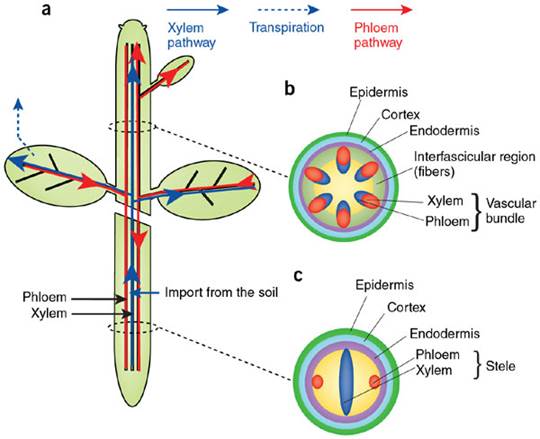

Phloem and xylem transporters

in plants; (a) Routes of long-distance transport in plants. The xylem

transport (blue) conducts water and nutrients from the root to the shoot. The

phloem flow (red) redistributes the photosynthetic products from the leaves to

roots and other sink tissues. (b,c) Shoot stem (b) and root (c) section schemes showing the disposition of the vascular

tissues. Hélène S Robert & Ji í Friml; http://www.nature.com/

í Friml; http://www.nature.com/

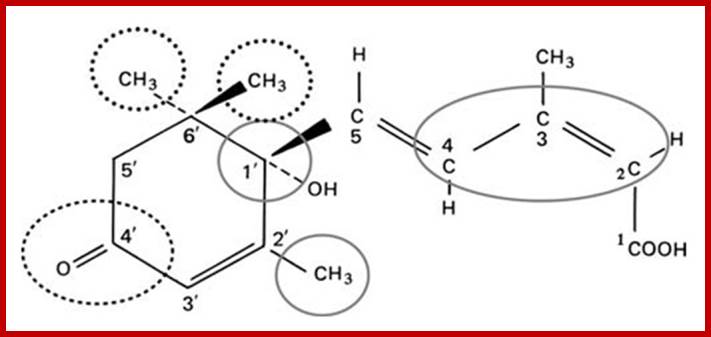

Abscissin I is a sesquiterpene consisting of 3 isoprenoid units. It has a 6-carbon ring and a 5-carbon chain ending with a carboxyl group. The ring has a double bonded oxygen group. However, naturally accuring ABA exists in two stereo isomeric forms like ABA (+) and ABA (-) but the active form is ABA (-).

Structure of ABA; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

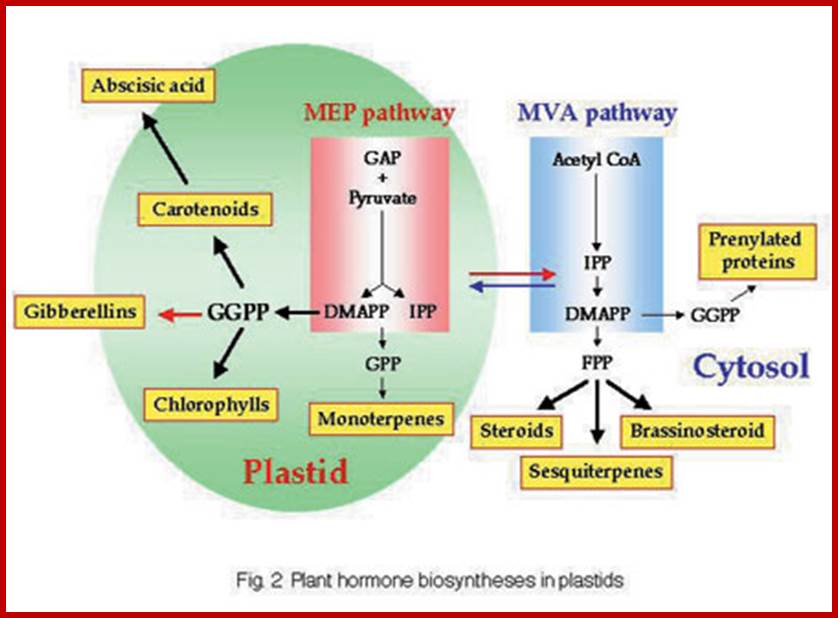

The biosynthetic pathway of ABA is almost similar to that of Gibberellins. In fact, mevolonate acts as the precursor. But some research workers consider that ABA is a break down product of violoxanthin, however, the detailed studies, using radioactive isotopes as labels, have revealed that it is derived from simple isoprenoid compounds and not from violoxanthin or such products.

The site of synthesis of ABA has been identified as plastids, which includes proplastids, etiolated and also mature chloroplasts. The initial biosynthetic reactions are more or less the same as that of GA up to Farnesyl pyrophosphate FPP and GGMP. From GGMPP onwards, the synthesis of GA and ABA go through two different pathways; which is controlled by phytochrome, water stress and environmental factors. Depending upon the factors, one pathway is favored over the other. Adverse environmental factors like water stress, salt stress and severe cold favor the synthesis of ABA. But red light favorable conditions enhance the synthesis of GAs.

http://devids.net/plant-hormones

Thus plastids play an important role in regulating the synthesis of anyone of these two hormones GA and ABA or both at any given time depending upon phytochrome state or water potential of the cell.

Biosynthetic pathway of ABA and its action; Plant cell Biology; www.seehint.com

Pathway and Regulation of ABA Biosynthesis.

ABA is synthesized from a C40 precursor β-carotene via the oxidative cleavage of neoxanthin and a two-step conversion of xanthoxin to ABA via ABA-aldehyde. Environmental stress such as drought, salt and, to a lesser extent, cold stimulates the biosynthesis and accumulation of ABA by activating genes coding for ABA biosynthetic enzymes. Stress activation of ABA biosynthetic genes is probably mediated by a Ca2+-dependent phosphorelay cascade, as shown at left. In addition, ABA can feedback stimulate the expression of ABA biosynthetic genes, also likely through a Ca2+-dependent phosphoprotein cascade (Xiong et al., 2001a, 2002; L. Xiong and J.K. Zhu, unpublished data). Also indicated is the breakdown of ABA to phaseic acid. AAO, ABA-aldehyde oxidase; MCSU, molybdenum cofactor sulfurase; NCED, 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase; ZEP, zeaxanthin epoxidase.

Effects of ABA:

Dormancy:

Abscisic acid is a stress induced hormone. During winter season in temperate and cold regions, most of the axillary and terminal buds undergo a period of suspended physiological activities called a period of dormancy. Even seeds belonging to various species exhibit dormancy; which has been attributed to ABA’s effect on physiological activities of the cells.

Studies on ABA’s effect on transcription and translation indicate, the hormone inhibits RNA polymerase activity. Its effect on translation has been attributed to its inductive ability to synthesize a RNA species, which is poly (A) rich a (mol. Wt. of 10,000 Daltons). This poly-(A) RNA is capable of inhibiting the translation of mRNA by hybridizing with 3’ region of mRNA. Thus it affects both transcription and translation. During the seed development or during induction of dormancy transcriptional activity has been found to be normal but the mRNA synthesized is made inactive by ABA by the above said mechanism. Most of the mRNAs remain as inactive mRNPs or informosomes. Thus ABA imposes dormancy in the said structures like buds and seeds. ABA is also known to promote dehydration in seeds and render them dormant. How ABA brings about this effect is not clear, but it is known that ABA has profound effect on Ca+, K+ and H+ fluxes across the membranes.

ABA inhibits GA mediated α-amylase synthesis:

It is very interesting to know that one hormone interacts with another hormone in regulating the gene expression. Interestingly, both GA and ABA are synthesized in the plastids and they follow the same pathway in the initial steps. Curiously enough, both the said hormones inhibit each other’s physiological effects.

While Gibberellins activate aleurone cells to produce alfa amylase and proteases through differential gene expression, ABA completely inhibits the GA mediated synthesis of amylase and protease by inhibiting the translation of mRNA through ploy-A rich RNA. By another mechanism ABA also activates the release of specific short chain fatty acids that inhibits GA3 induced amylosis in barley endosperm by inhibiting transcription and translation of alfa amylase mRNAs.

Proposed model for the hormonal regulation of endosperm cap weakening and rupture(Linkies et al. 2009). Role of GA in countering ABA action during seed germination; http://www.seedbiology.de

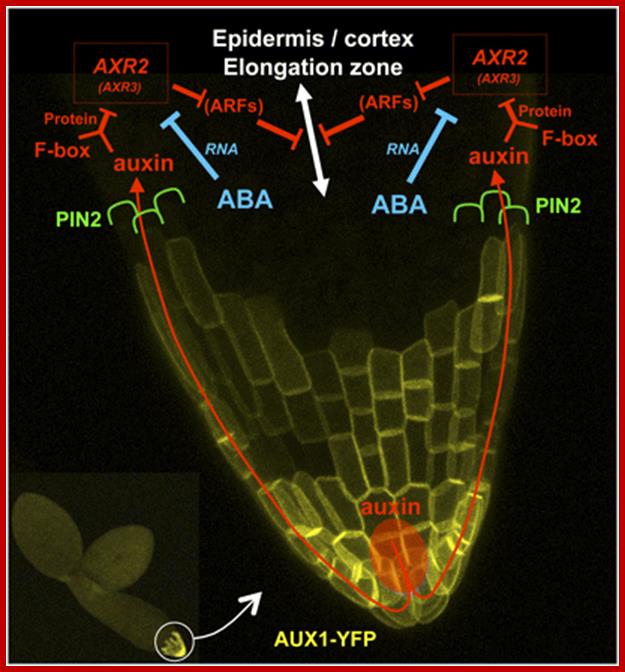

A Model of ABA and Auxin Crosstalk for the Repression of Embryonic Axis Elongation.; This model is drawn on a magnified confocal micrograph of the embryonic axis tip of a wild-type line expressing ProAUX1:AUX1-YFP (Figure 4; seeMethods). Auxin (red) is distributed from the radicle tip to the elongation zone via the influx facilitator AUX1 located in the root cap (yellow) and the efflux carrier PIN2 polarly localized in the elongating epidermal and cortical cells (green). In the elongation zone, auxin activates its signaling pathway (red) by binding to TIR1/AFB F-box proteins, promoting the degradation of the Aux/IAA repressors AXR2/IAA7 and possibly AXR3/IAA17. This would, in turn, activate unknown transcriptional regulator ARFs to repress cell elongation. ARFs appear in brackets because their involvement in ABA- and auxin-dependent repression of embryonic axis elongation remains speculative. We propose that ABA (blue) potentiates the auxin pathway by strongly decreasing the mRNA levels of the Aux/IAA repressor AXR2/IAA7 (and possiblyAXR3/IAA17).http://www.plantcell.org/

Effect on Cell Expansion:

Normal plants treated with GA or IAA exhibit pronounced growth by way of activating cell elongation, but ABA inhibits the cell growth considerably. Considering this, some botanists think that the genetic dwarfism is probably due to the presence of excess of ABA in their plant body. But quantitative studies reveal that there is no such correlation between the genetic dwarfism and ABA content. And genetic dwarfism is rather due to the deficiency of Gibberellins than to the presence of excess ABA. But the inhibitory effect of ABA has been attributed to its effects on membrane permeability and ion fluxes. It is well known that ABA brings about the extrusion of K+ ions from guard cells and causes closing of the stomata. Thus ABA may act on other cells as in the case of guard cells and inhibit GA or IAA mediated cell elongation.

Senescence:

Abscisic acid is known to initiate aging in leaves in which process the detached leaves loose their green color and becomes yellow. During ABA induced senescence, degreening takes place by the synthesis of an enzyme called chlorophyllase, whose synthesis can be blocked by transcriptional or translational inhibitors. ABA also induces high rate of respiration for only a short period of time. The labalizing effect of ABA on lysosomes leads to the release of enzymes, which start degrading cellular macromolecules. Photosynthesis and other anabolic processes like protein synthesis, etc., are greatly reduced. The induction of ethylene synthesis is believed to be activated by ABA in certain cases, where the auxin concentration is very low. The ABA induced ethylene in turn causes the formation of abscission layers in the stalks of leaves and fruits.

On the other hand, cytokinins are known to overcome ABA’s effect, by decreasing degradative processes.

ABA influences the formation of abscission layer. This process has been exploited commercially in harvesting fruits and cotton balls. By spraying ABA on cotton plants, most of the stalks of cotton balls develop abscission layers simultaneously and it will greatly help in mechanical harvesting of cotton balls. Similarly, in fruit orchards, to obtain uniform harvesting, controlled application of ABA facilitates the harvesting of most of the fruits at one time.

Effect on Turgour Movement:

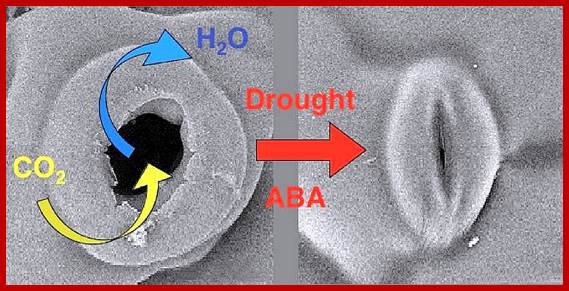

In recent years, ABA’s effect on membranes, in changing ion fluxes, is drawing the attention of all plant physiologists. ABA has a positive effect on guard cells, where the cells loose most of the K+ ions to subsidiary cells and collapse to induce the closing of the stomata. In fact, guard cells also contain chloroplasts and it is suspected that ABAs are released from them under certain conditions like water stress or high temperatures, which in fact induce the closing of the stomata.

ABA induced stomatal closure; www.gopixpic.com

Stomatal movement in closing and opening of guard cell is an excellent system in understanding interaction of cellar and external factors. Co2 depletion in the atmosphere, water stress leads to activation of ABA that is released from chloroplast found in guard cells. They activate Potassium and H-channels for expulsion of ions and another class of channels opens for inward movement of Ca+ ions. This leads to the closing of the stomata; this process is reverse of opening, where K+ ions are translocated in to build up of ion concentration so as to facilitate the movement of water into guard cells, so the cells turgour pressure increase and stomata opens.

The Clickable Guard Cell: Electronically linked

Model of Guard Cell Signal Transduction Pathways;

Guard cells are located in the leaf epidermis and pairwise surround stomatal pores, which allow CO2 influx for photosynthetic carbon fixation and water loss via transpiration to the atmosphere. Signal transduction mechanisms in guard cells integrate a multitude of different stimuli to modulate stomatal aperture. Stomata open in response to light. In response to drought stress, plants synthesize the hormone abscisic acid (ABA) which triggers closing of stomatal pores. Guard cells have become a well-developed system for dissecting early signal transduction mechanisms in plants and for elucidating how individual signaling mechanisms can interact within a network in a single cell. Previous reviews have described pharmacological modulators that affect guard cell signal transduction. Here we focus on mechanisms for which genes and mutations have been characterized, including signaling components for which there is substantial biochemical evidence such as ion channels which represent targets of early signal transduction mechanisms. Guard cell signaling pathways are illustrated as graphically linked models:Pascal Mäser et al;www.labs.biology.ucsd.edu

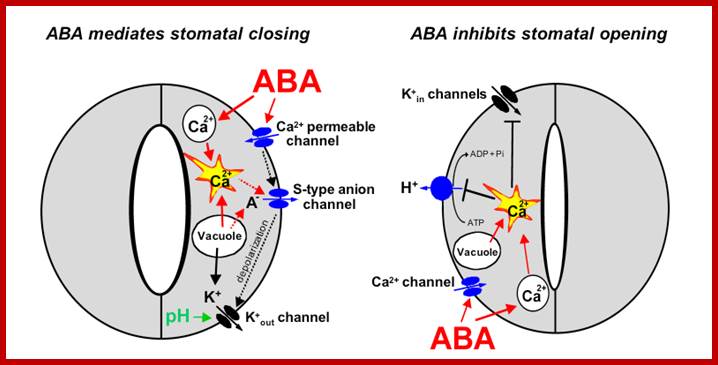

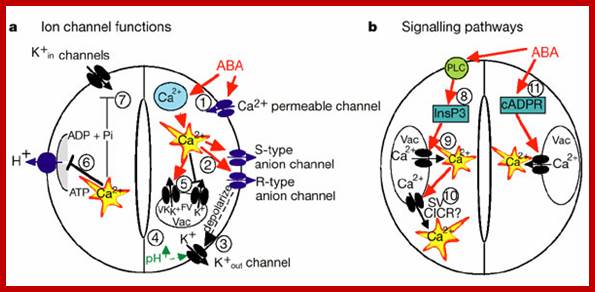

Components and pathways of guard cell ABA signalling; www.nature.com

a, ABA is detected by as yet unidentified receptors (right guard cell) and induces cytosolic Ca2+ elevations (1) through extracellular Ca2+influx and release from intracellular stores. [Ca2+]cyt elevations activate two types of anion channel that mediate anion release from guard cells, slow-activating sustained (S-type) or rapid transient (R-type) anion channel, (3) Anion efflux causes depolarization, which activates outward-rectifying K+ (K+out) channels and results in K+ efflux from guard cells2, 3. (4) ABA causes an alkalization of the guard cell cytosol, which enhances K+out channel activity44. Overall, the long-term efflux of both anions and K+ from guard cells contributes to the loss of guard cell turgor, leading to stomatal closing3. Over 90% of the ions released from the cell during stomatal closing must be first released from vacuoles into the cytosol. (5) At the vacuole, [Ca2+]cyt elevation activates vacuolar K+ (VK) channels, which are thought to mediate Ca2+-induced K+ release from the vacuole8. In addition, fast vacuolar (FV) channels can mediate K+ efflux from guard cell vacuoles at resting [Ca2+]cyt45. ABA also inhibits ion uptake, which is required for stomatal opening (left guard cell). (6) [Ca2+]cyt elevations inhibit the electrogenic plasma membrane proton-extruding H+-ATPases and K+ uptake (K+in) channels (7). Initiation of ion efflux (1–5, right guard cell) and inhibition of stomatal opening processes left guard cell) provide a mechanistic basis for ABA-induced stomatal closing.

b, Ca2+-releasing second messengers that mediate ABA-induced stomatal closing. Second messengers have been implicated in ABA signalling in guard cells, including InsP3 and cADPR. (8) Biochemical evidence indicates that ABA stimulates InsP3 production in guard cells2. InsP3 can release Ca2+ from intracellular stores, inhibit K+in channels and cause stomatal closure. (10) [Ca2+]cyt elevations may be amplified by a Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) mechanism from the vacuole through activation of the Ca2+-dependent slow vacuolar (SV) channel Data questioning this SV model for CICR and recent other data supporting it indicate the potential for molecular genetic analyses.) ABA stimulates the production of cADPR in plant cells, which also increases [Ca2+]cyt in guard cells and promotes stomatal closing. www.nature.com

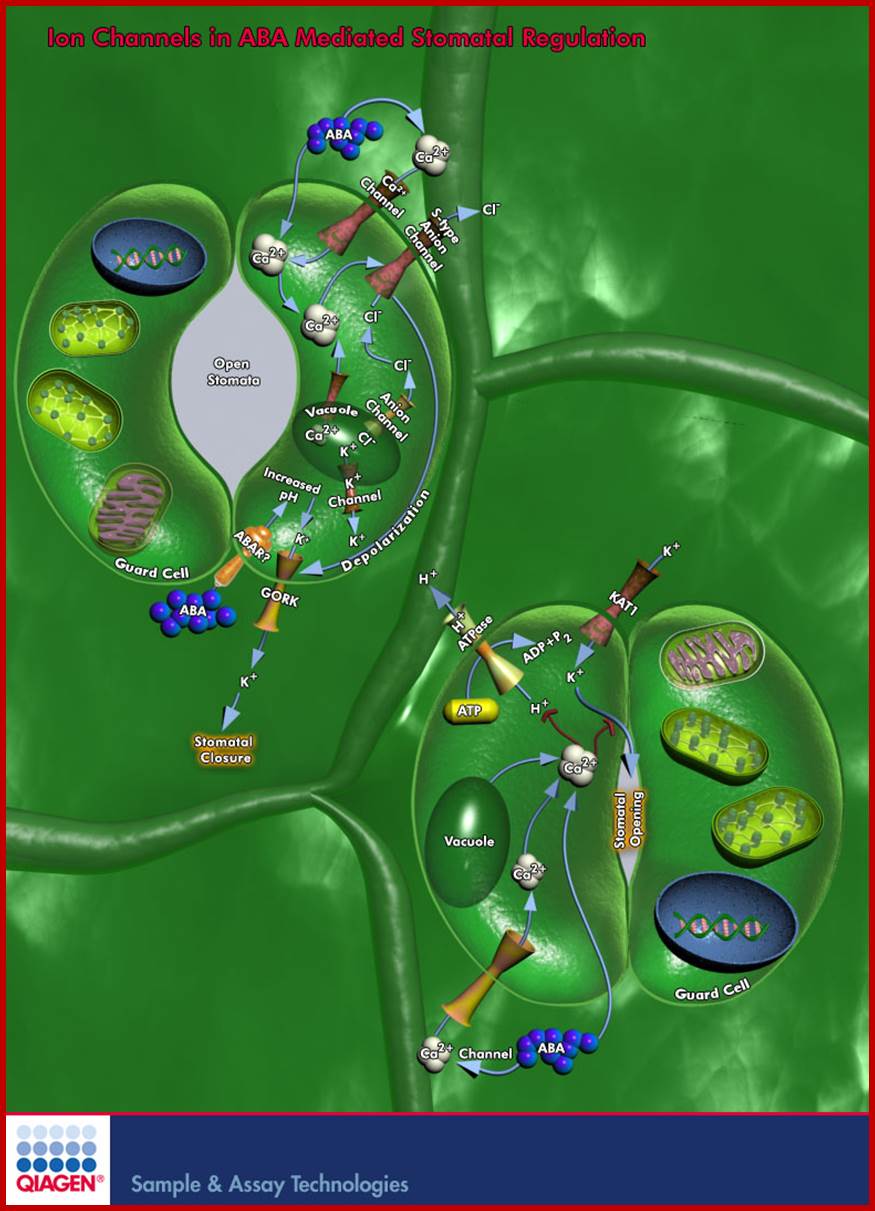

Ion Channels in ABA Mediated Stomatal Regulation; Quaigen

Plant growth and development are regulated by Internal Signals and by External Environmental Conditions. One important regulator that coordinates growth and development with responses to the environment is the Sesquiterpenoid hormone ABA (Abscisic Acid). ABA plays important roles in many cellular processes including Seed Development, Dormancy, Germination, Vegetative Growth, Leaf Senescence, Stomatal Closure, and Environmental Stress Responses. ABA is synthesized in almost all cells, but its transport from roots to shoots and the recirculation of ABA in both Xylem and Phloem are important aspects of its physiological role. The most extensively investigated developmental and physiological effects of ABA are those involved in Seed Maturation and Dormancy and in the Regulation of Stomata. These diverse functions of ABA involve complex regulatory mechanisms that control its production, degradation, signal perception, and transduction ; www.qiagen.com

Simplified model for the roles of ion

channels and pumps in regulating stomatal movements. Note that other 2nd messengers in addition

to Ca2+ also function in stomatal movements (see text for details). Mouse-over

for explanations (may not work on all browsers). The hormone ABA triggers a

signalling cascade in guard cells that results in stomatal closure and inhibits

stomatal opening. Stomatal closure is mediated by turgor reduction in guard

cells, which is caused by efflux of K+ and

anions from guard cells, sucrose removal, and a parallel conversion of the

organic acid malate to osmotically inactive starch (MacRobbie, 1998).

Figure 1 shows an extension of early models for the roles of ion channels in

ABA-induced stomatal closing (Schroeder and Hedrich, 1989; McAinsh et al., 1990). ABA

triggers cytosolic calcium ([Ca2+]cyt)

increases (left panel; McAinsh et al., 1990). [Ca2+]cyt elevations activate two different

types of anion channels: Slow-activating sustained (S-type; Schroeder and

Hagiwara, 1989 ) and

rapid transient (R-type; Hedrich et al., 1990) anion

channels. Both mediate anion release from guard cells, causing depolarization

(left panel). This change in membrane potential deactivates inward-rectifying K+ (K+in)

channels and activates outward-rectifying K+ (K+out) channels (Schroeder et al., 1987),

resulting in K+ efflux from guard cells (left panel).

In addition, ABA causes an alkalization of the guard cell cytosol (Blatt and Armstrong, 1993) which

directly enhances K+out channel activity (Blatt and Armstrong, 1993; Ilan et al., 1994; Miedema and Assmann, 1996) and

down-regulates the transient R-type anion channels (Schulz-Lessdorf et al., 1996). The

sustained efflux of both anions and K+ from

guard cells via anion and K+out channels contributes to loss of guard

cell turgor, which leads to stomatal closing (left panel). As vacuoles can take

up over 90% of the guard cell’s volume, over 90% of the ions exported from the

cell during stomatal closing must first be transported from vacuoles into the

cytosol (MacRobbie,

1998; MacRobbie, 1995). [Ca2+] elevation activates vacuolar K+ (VK) channels proposed to provide a

pathway for Ca2+-induced K+ release from the vacuole (Ward and Schroeder, 1994). At

resting [Ca2+]cyt, K+ efflux from guard cell vacuoles can be

mediated by fast vacuolar (FV) channels, allowing for versatile vacuolar K+ efflux pathways (Allen and Sanders, 1996). The pathways

for anion release from vacuoles remain elusive.

Stomatal opening is driven by plasma membrane

proton-extruding H+-ATPases. H+-ATPases can drive K+ uptake via K+in channels (right panel; Kwak et al., 2001).

Cytosolic [Ca2+] elevations in guard cells

down-regulate both K+in channels (Schroeder and

Hagiwara, 1989) and plasma membrane H+-ATPases (Kinoshita et al., 1995),

providing a mechanistic basis for ABA and Ca2+ inhibition

of K+ uptake during stomatal opening (right

panel). http://labs.biology.ucsd.edu/

A model for roles of ion channels in ABA signaling.

Mouse-over for explanations or see text below (mouse-over

does not work on

ABA triggers cytosolic calcium ([Ca2+]cyt) increases

(McAinsh et al., 1990; Fig. 1, left panel). [Ca2+]cyt elevations activate two different

types of anion channels: Slow-activating sustained (S-type) and rapid transient

(R-type; Hedrich et al., 1990) anion channels. Both mediate anion release from

guard cells, causing depolarization (Fig. 1, left panel). This change in membrane

potential deactivates inward-rectifying K+(K+in)

channels and activates outward-rectifying K+ (K+out) channels

(Schroeder et al., 1987), resulting in K+ efflux from guard cells (Fig. 1, left panel). In addition, ABA

causes an alkalization of the guard cell cytosol (Blatt and Armstrong, 1993)

which directly enhances K+out channel activity (Blatt and Armstrong,

1993; and down-regulates the

transient R-type anion channels (Schulz-Lessdorf et al., 1996). The sustained

efflux of both anions and K+ from

guard cells via anion and K+out channels contributes to loss of guard

cell turgor, which leads to stomatal closing.

As vacuoles can take up over 90% of the guard cell’s volume, over 90% of the ions exported from the cell during stomatal closing must first be transported from vacuoles into the cytosol ( MacRobbie, 1995). [Ca2+]cyt elevation activates vacuolar K+ (VK) channels proposed to provide a pathway for Ca2+-induced K+ release from the vacuole. At resting [Ca2+]cyt, K+ efflux from guard cell vacuoles can be mediated by fast vacuolar (FV) channels, allowing for versatile vacuolar K+ efflux pathways. The pathways for anion release from vacuoles remain elusive.

Stomatal opening is driven by plasma membrane proton-extruding H+-ATPases.

H+-ATPases can drive K+uptake via K+in channels (Fig. 1, right panel; .

Cytosolic Ca2+ elevations

in guard cells down-regulate both K+in channels and plasma membrane H+-ATPases

providing a mechanistic basis for ABA and Ca2+ inhibition of K+ uptake during stomatal opening.

Light induced

stomatal opening: Guard cells respond to a multitude of signals including

temperature, partial CO2 pressure,

light, humidity, and hormonal stimuli. For the majority of signals the

molecular identity of the sensors is not known, with the notable exception of

blue light: The Phototropins- PHOT1 and PHOT2

were shown to be the blue light receptors in Arabidopsis guard cells). Figure above illustrates the signaling cascade from

activation of PHOT1,2 to stomatal opening in terms of known genes and their

relative position in the signal transduction pathway.

ABA induced

stomatal closing: One of the best understood plant signaling networks is the one

triggered by ABA in guard cells, causing stomatal closure. As shown in Figure, many genes encoding for

positive as well as negative regulators of guard cell ABA signaling have been

identified in Arabidopsis.

The gene(s) encoding the ABA receptor(s), however, remained elusive. Most of

the ABA signal transduction components were found by classic

"forward" genetic screens for either increased or reduced sensitivity

to ABA.

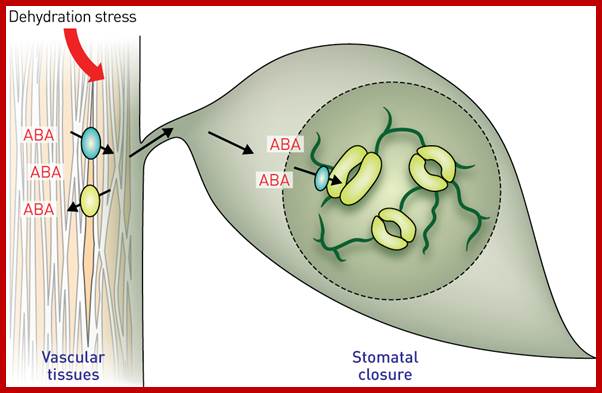

Interrogating a messenger of plant stress; Identifying the molecular transporters that drive plant responses to drought and salinity could assist in the development of stress-resistant crop varieties;in response drought ABA is synthesized in ven leaves and the same is transported nearby stomatal guard cells specialized transporters

http://www.riken.jp/

Similarly, the turgour movements of motor or bulliform cells in grass leaves, turgour movements of parenchymatous cells in the pulvinous of Mimosa pudica and other plants which exhibit nastic movements are believed to be due to the action of ABA. In recent years, the role of ABA in photo induced growth curvatures has been gaining importance. When stem tips are unilaterally illuminated from one side, the cells that receive light release some quantity of ABA, which causes the efflux of K+ ions, which results in the collapsing of cells. At the same time, they also inhibit cell elongation. But on the other side i.e. darker side cells grow normally and bring about growth curvatures. It look like ABA by their controlled synthesis and release bring about innumerable physiological is plants effects.

ABA and Gene Expression:

ABA-mediated transcriptional regulation in response to osmotic stress in plants:

Fujita Y1, Fujita M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K.

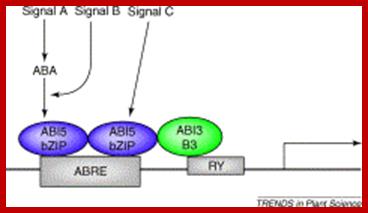

The plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA) plays a pivotal role in a variety of developmental processes and adaptive stress responses to environmental stimuli in plants. Cellular dehydration during the seed maturation and vegetative growth stages induces an increase in endogenous ABA levels, which control many dehydration-responsive genes. In Arabidopsis plants, ABA regulates nearly 10% of the protein-coding genes, a much higher percentage than other plant hormones. Expression of the genes is mainly regulated by two different families of bZIP transcription factors (TFs), ABI5 in the seeds and AREB/ABFs in the vegetative stage, in an ABA-responsive-element (ABRE) dependent manner. The SnRK2-AREB/ABF pathway governs the majority of ABA-mediated ABRE-dependent gene expression in response to osmotic stress during the vegetative stage. In addition to osmotic stress, the circadian clock and light conditions also appear to participate in the regulation of ABA-mediated gene expression, likely conferring versatile tolerance and repressing growth under stress conditions. Moreover, various other TFs belonging to several classes, including AP2/ERF, MYB, NAC, and HD-ZF, have been reported to engage in ABA-mediated gene expression. This review mainly focuses on the transcriptional regulation of ABA-mediated gene expression in response to osmotic stress during the vegetative growth stage in Arabidopsis.

ABA is also activates gene expression of ABA response factor (TFs), binds to upstream binding sequences. Activation leads to the production of factors that provide stress tolerance.

ABA is involved in a variety of stress tolerance activities such osmotic stress, cold stress, superoxide (ROS) stress, salt stress and others. Only diagrams have been provided they are self explanatory in nature. In response to ABA couple hundred gene are expressed.

The 1173 ABA-regulated genes of guard cells identified by our study share significant overlap with ABA-regulated genes of other tissues, and are associated with well-defined ABA-related promoter motifs such as ABREs and DREs

ABA response elements ABRE core is ACGT contains CGMCACGTGB motif and it is responsive coexpresed genes in rice In angiosperms (Magnoliophyta), ABA-induced gene expression is mediated by promoter elements such as the G-box-like ACGT-core motifs recognized by bZIP transcription factors. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

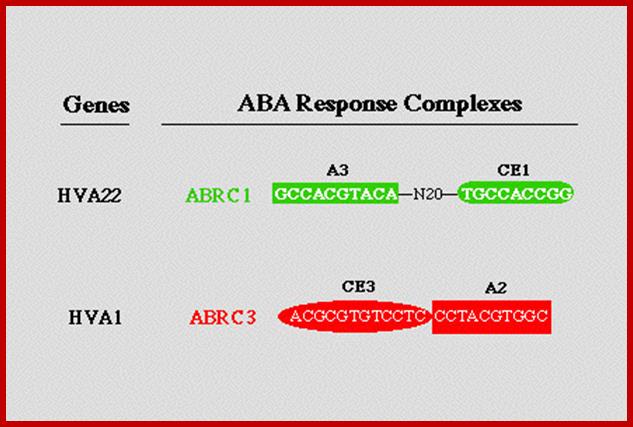

About two-thirds of drought-responsive genes (1310 out of 1969) were regulated by ABA and/or the ABA analogue PBI425. http://jxb.oxfordjournals.org/our data suggest that G-box sequences are necessary but not sufficient for ABA response. Instead, an ABA response complex consisting of a G-box, namely, ABRE3 (GCCACGTACA), and a novel coupling element, CE1 (TGCCACCGG), is sufficient for high-level ABA induction, and replacement of either of these sequences abolishes ABA responsiveness. http://www.plantcell.org/https://www.academia.edu/ . http://bmcgenomics.biomedcentral.com/

http://epigeneticsofplantinstress.weebly.com/salinity.html

"ABA Response Complex (ABRCs): promoter switches which are necessary and sufficient for ABA induced gene expression"; www.biology.wustl.edu

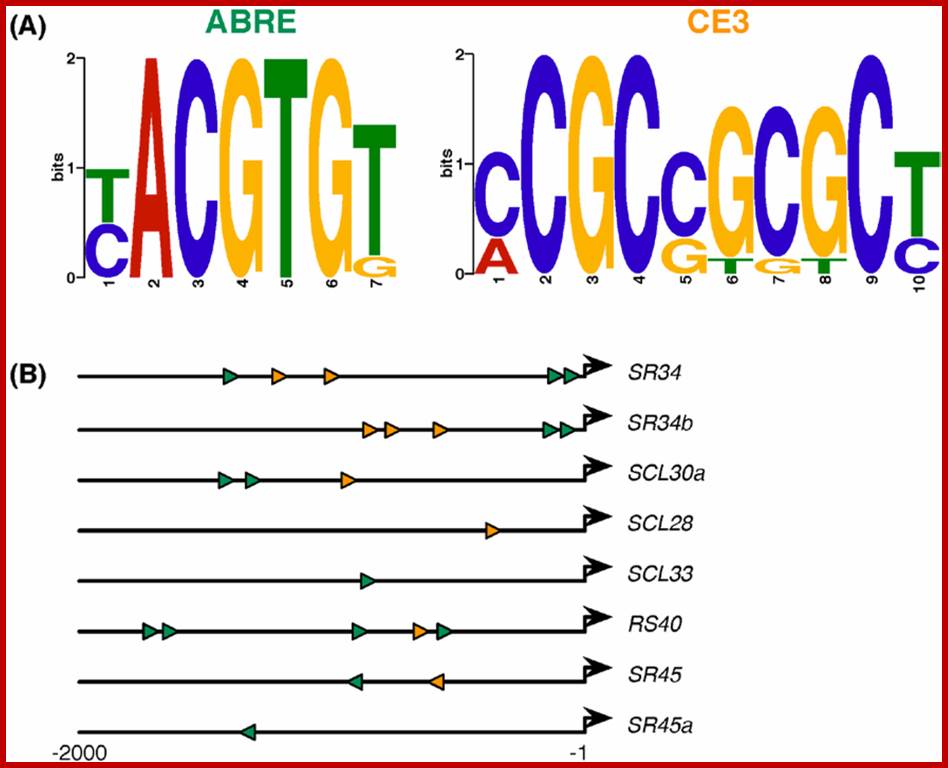

ABA-responsive cis-element consensus sequences and their locations/orientations in the eight SR/SR-like genes responsive to ABA and/or alterations in the ABA pathway. (A) The ABRE (7 bp) and CE3 (10 bp) motif logos as generated by MEME [86] based on previously reported motifs [84]; and (B) Schematic representation of the relative position and orientation of ABRE (green) and CE3 (orange) elements found in the 2 kb upstream sequences of the SR or SR-like genes found to respond to any of the ABA scenarios analyzed (see Figure 2,Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). The bold black arrows denote the transcription start sites. Exact coordinates of the elements are presented in ; http://epigeneticsofplantinstress.weebly.com/salinity.html

This review focuses mainly on eudicot seeds, and on the interactions between abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellins (GA), ethylene, brassinosteroids (BR), auxin and cytokinins in regulating the interconnected molecular processes that control dormancy release and germination. Signal transduction pathways, mediated by environmental and hormonal signals, regulate gene expression in seeds. Seed dormancy release and germination of species with coat dormancy is determined by the balance of forces between the growth potential of the embryo and the constraint exerted by the covering layers, e.g. testa and endosperm. Recent progress in the field of seed biology has been greatly aided by molecular approaches utilizing mutant and transgenic seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana and the Solanaceae model systems, tomato and tobacco, which are altered in hormone biology. ABA is a positive regulator of dormancy induction and most likely also maintenance, while it is a negative regulator of germination. GA releases dormancy, promotes germination and counteracts ABA effects. Ethylene and BR promote seed germination and also counteract ABA effects. We present an integrated view of the molecular genetics, physiology and biochemistry used to unravel how hormones control seed dormancy release and germination. Birgit Kucera, Marc Alan Cohn, Gerhard Leubner-Metzger; Hormonsl Interactions during seed dormancy; www.seedbiology.de

Distinction between siganal A and signal B and C can be measured by the levels of ABA in response to signals; www.cell.com; http://epigeneticsofplantinstress.weebly.com/salinity.html

ABA-responsive cis-element consensus sequences and their locations/orientations in the eight SR/SR-like genes responsive to ABA and/or alterations in the ABA pathway. (A) The ABRE (7 bp) and CE3 (10 bp) motif logos as generated by MEME [86] based on previously reported motifs [84]; and (B) Schematic representation of the relative position and orientation of ABRE (green) and CE3 (orange) elements found in the 2 kb upstream sequences of the SR or SR-like genes found to respond to any of the ABA scenarios analyzed (see Figure 2,Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). The bold black arrows denote the transcription start sites. Exact coordinates of the elements are presented in; http://epigeneticsofplantinstress.weebly.com/salinity.html

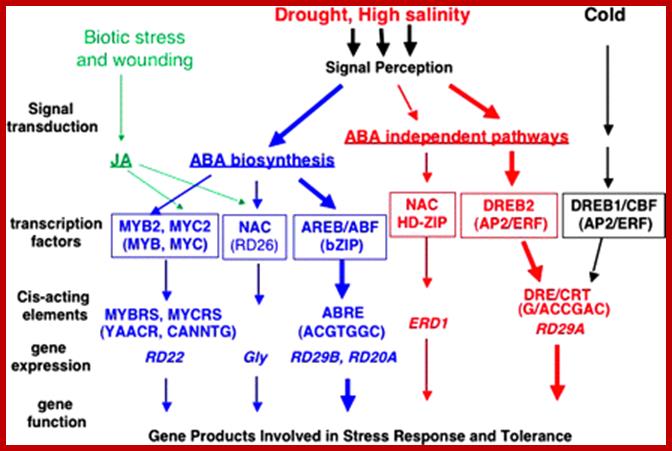

Transcriptional regulatory networks of abiotic stress signals and gene expression. At least six signal transduction pathways exist in drought, high salinity, and cold-stress responses: three are ABA dependent and three are ABA independent. In the ABA-dependent pathway, ABRE functions as a major ABA-responsive element. AREB/ABFs are AP2 transcription factors involved in this process. MYB2 and MYC2 function in ABA-inducible gene expression of the RD22 gene. MYC2 also functions in JA-inducible gene expression. The RD26 NAC transcription factor is involved in ABA- and JA-responsive gene expression in stress responses. These MYC2 and NAC transcription factors may function in cross-talk during abiotic-stress and wound-stress responses. In one of the ABA-independent pathways, DRE is mainly involved in the regulation of genes not only by drought and salt but also by cold stress. DREB1/CBFs are involved in cold-responsive gene expression. DREB2s are important transcription factors in dehydration and high salinity stress-responsive gene expression. Another ABA-independent pathway is controlled by drought and salt, but not by cold. The NAC and HD-ZIP transcription factors are involved in ERD1 gene expression. http://jxb.oxfordjournals.org/

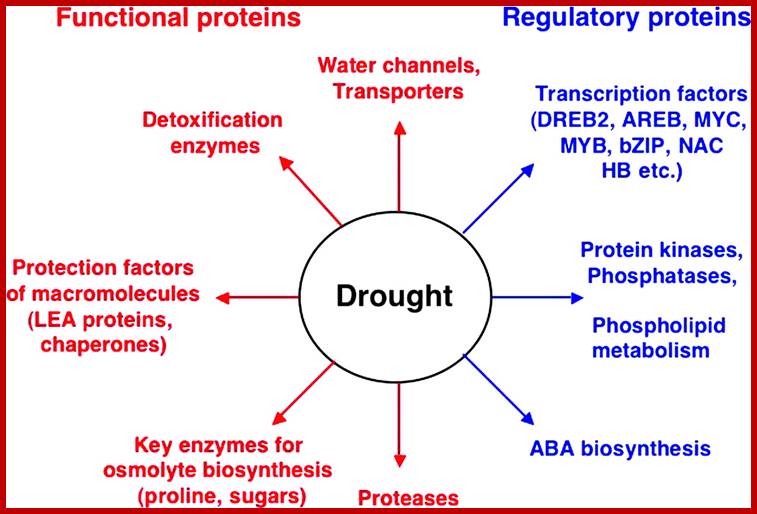

Draught:

Functions of drought stress-inducible genes in stress

tolerance and response. Gene products are classified into two groups. The first

group includes proteins that probably function in stress tolerance (functional

proteins), and the second group contains protein factors involved in further

regulation of signal transduction and gene expression that probably function in

stress response (regulatory proteins). www.jxb.oxfordjournals.org

Functions of drought stress-inducible genes in stress

tolerance and response. Gene products are classified into two groups. The first

group includes proteins that probably function in stress tolerance (functional

proteins), and the second group contains protein factors involved in further

regulation of signal transduction and gene expression that probably function in

stress response (regulatory proteins). www.jxb.oxfordjournals.org

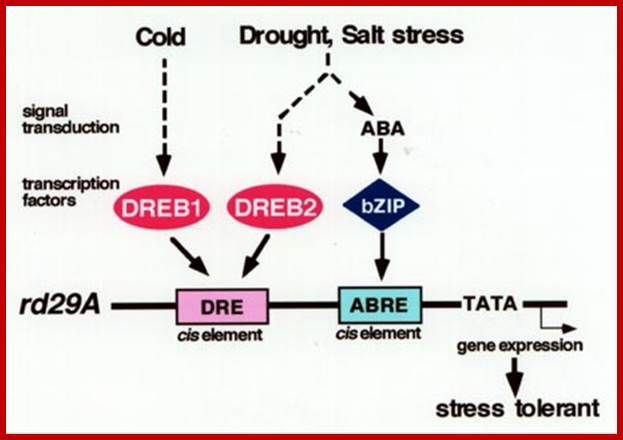

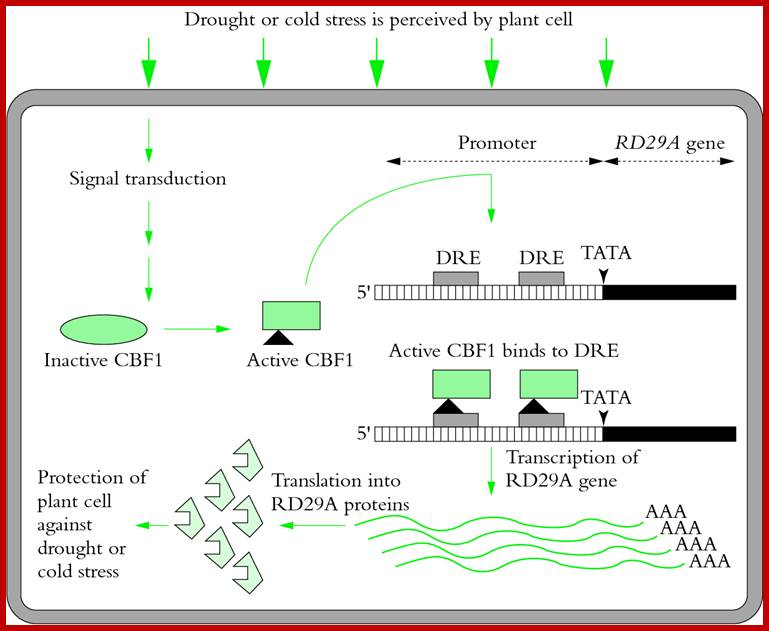

There are at least two independent signal transduction pathways—ABA independent and ABA responsive—between environmental stress and expression of the rd29A gene. The DRE functions in the ABA-independent pathway, and the ABA-responsive element (ABRE) is one of the cis-acting elements in the ABA-responsive induction of rd29A. Two independent families of DRE binding proteins, DREB1 and DREB2, function as trans-acting factors and separate two signal transduction pathways in response to cold, and drought and high-salinity stresses, respectively. bZIP, basic leucine zipper.www.plantcell.org

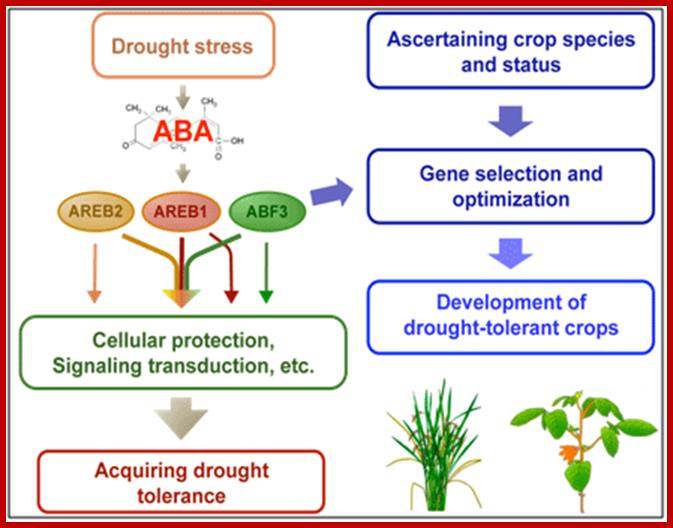

Model for the development of abiotic stress-tolerant crops using three kinds of AREB-type transcription factors that cooperatively regulate ABA-mediated drought stress tolerance. AREB1, AREB2 and ABF3 cooperatively regulate the ability of plants related to drought tolerance. While the transcription factors have overlapping functions, each of them has its own specific roles .https://www.jircas.affrc.go.jp

Ros response involves dsRNA mediated mi RNA; www.intechopen.com

RD29A gene in Arabidopsis responds to draught and cold stress; leads to activation of DNA binding proteins called CBE1 which then binds to specific response elements DRE,found in gene promoter elements; this leads to enhanced transcription and leads to the production of protein RD29A protect the cell against draught and cold.; plantsin action. www.science.uq.edu.au

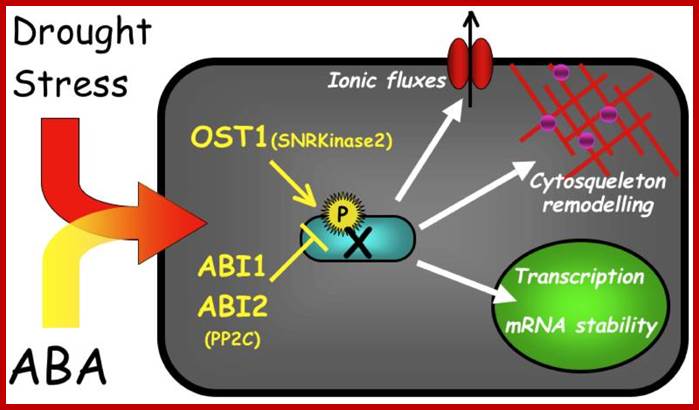

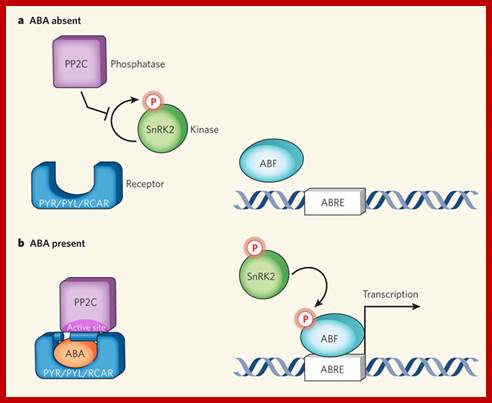

Minimal abscisic acid (ABA) signalling pathway;a, In the absence of the plant hormone ABA, the phosphatase PP2C is free to inhibit autophosphorylation of a family of SnRK kinases. b, ABA enables the PYR/PYL/RCAR family of proteins to bind to and sequester PP2C (see Figure 2, overleaf, for mechanistic details). This relieves inhibition on the kinase, which becomes auto-activated and can subsequently phosphorylate and activate downstream transcription factors (ABF) to initiate transcription at ABA-responsive promoter elements (ABREs).Laura B.Sheard and Ning Zheng; www.nature.com.

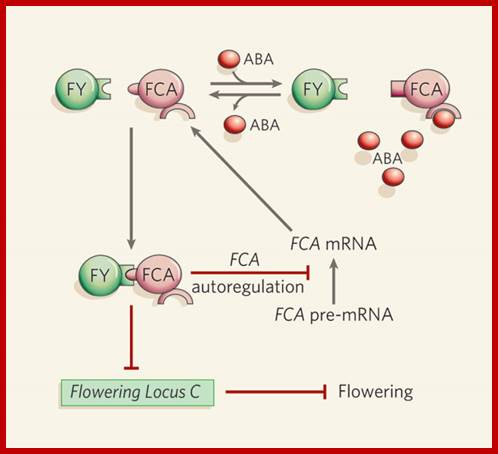

Abscisic acid, RNA metabolism and control of flowering in plants; Binding of two proteins, FCA and FY, to one another results in a decrease in expression levels of Flowering Locus C (FLC), causing a transition from vegetative growth to flowering. The FCA–FY complex also causes synthesis of a truncated, non-functional FCA messenger RNA in a negative feedback loop that results in fewer full-length FCA mRNA transcripts and less FCA protein6, 7. Razem et al. report that binding of abscisic acid (ABA) to FCA abolishes the interaction of FCA with FY, leading to an increase in full-length FCA transcripts and — through increased FLC activity — a delay in flowering. Red lines depict negative regulation. (Diagram modified from a figure provided by R. Hill.) Schroeder & Josef M Kuhn; www.nature.com

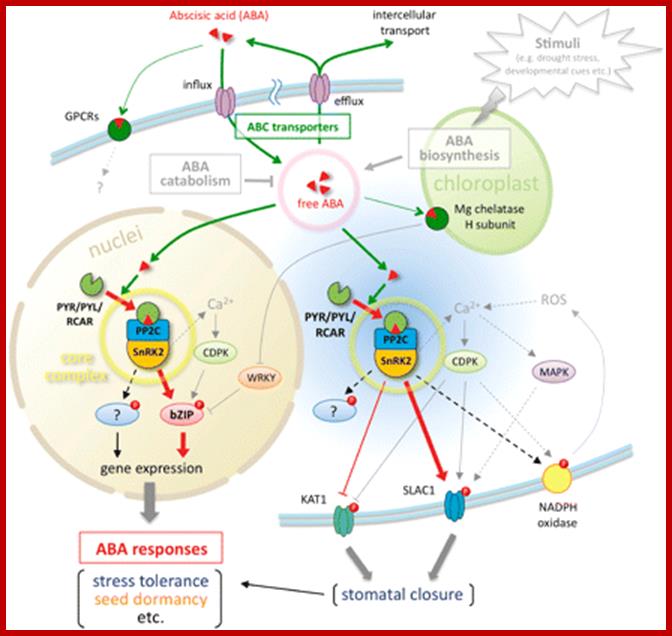

Overview of ABA sensing, signaling and transport; The ABA-related components described in this review are summarized. PYR/PYL/RCAR, PP2C and SnRK2 form a core signaling complex (yellow circle), which functions in at least two sites. One is the nucleus, in which the core complex directly regulates ABA-responsive gene expression by phosphorylation of AREB/ABF-type transcription factors. The other is the cytoplasm, and the core complex can access the plasma membrane and phosphorylate anion channels (SLAC1) or potassium channels (KAT1) to induce stomatal closure in response to ABA. Other substrates of SnRK2s have yet to be identified. The principal mechanism of ABA sensing or signaling in the core signaling complex is illustrated in Fig. 2. In contrast, the endogenous ABA level is a major determinant of ABA sensing that is maintained by ABA biosynthesis, catabolism or transport. The ABA transport system consists of two types of ABC transporter for influx or efflux. Although ABA biosynthesis and catabolism were not the focus of this review, these types of regulation are well described in other reviews (e.g. Nambara and Marion-Poll 2005, Hirayama and Shinozaki 2010). ABA movements are indicated by green lines and arrows, and major signaling pathways are indicated by red lines and arrows. Dotted lines indicate indirect or unconfirmed connections. http://pcp.oxfordjournals.org/

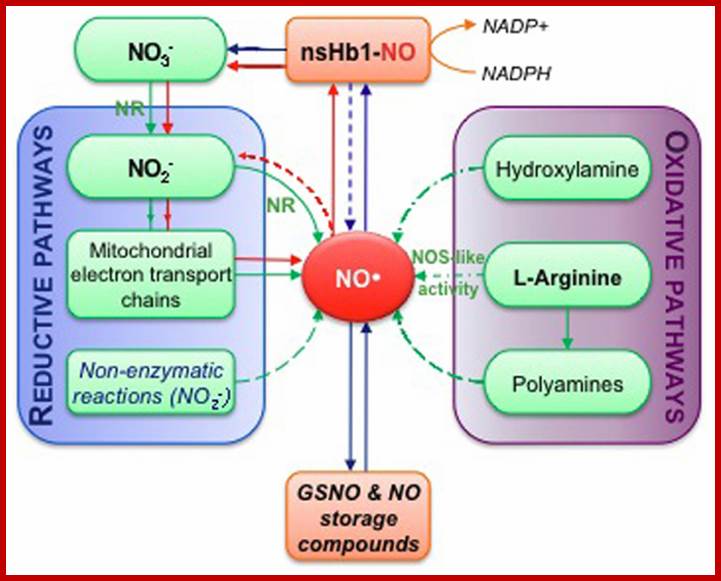

Simplified overview of NO biosynthesis and homeostasis in plant cells. This scheme is inspired from Moreau et al. (2010). Nitrate (NO−3 ) assimilation produces nitrite (NO−2 ) in a reaction catalyzed by nitrate reductase (NR). The subsequent reduction of nitrite into NO can occur enzymatically, either through NR activity or mitochondrial electron transport chains, and via non-enzymatic reactions (reductive pathways). Alternatively, NO synthesis can result from oxidative reactions from hydroxylamine, polyamines or L-arginine (L-Arg; oxidative pathways). NO synthesis from L-Arg could account for the nitric oxide synthase-like (NOS-like) activity detected in plants. The pool of NO is then influenced by non-symbiotic hemoglobin 1 (nsHb1) dioxygenase activity, which converts NO into NO−3 . NO can also react with reduced glutathione or thiol groups leading to the reversible formation of S-nitrosothiols (e.g., GSNO, S-nitrosoglutathione; S-nitrosylated proteins). Red arrows highlight the so-called nitrate-NO cycle that may take place under hypoxia. Green arrows correspond to biosynthesis reactions while blue arrows indicate reactions involved in NO; homeostasis. http://journal.frontiersin.org/

http://www.thericejournal.com/

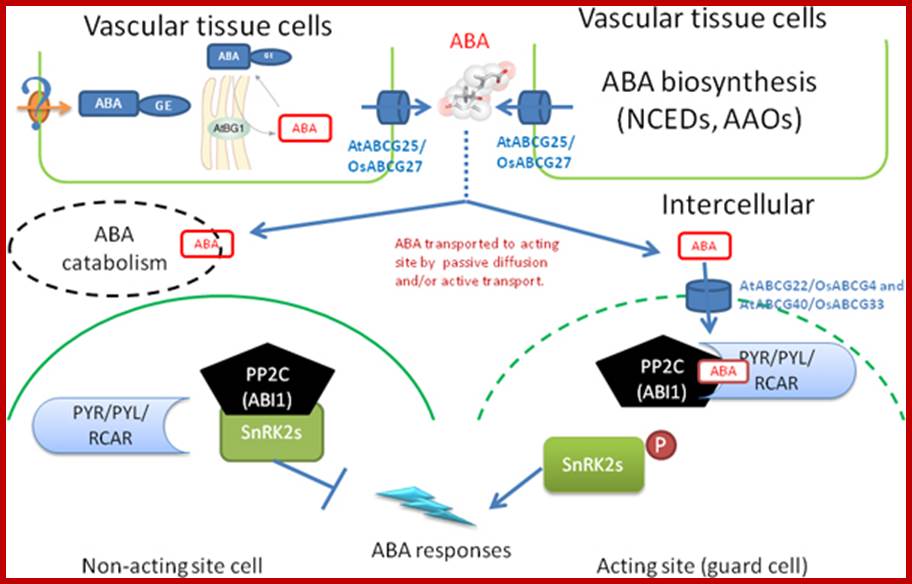

A simplified model for abscisic acid generation, transport and perception in plants. ABA biosynthesis is induced by environmental cues in the vascular tissues. ABA can also be released at ER from ABA-GE that stored in the vacuole or transported from the vacuolar system by an unknown ABA-GE transporter (? stand for unknown a mechanism). Both sourced ABAs are transported to intercellular space by the ABA transporters, AtABCG25 which majorly located in vascular tissue and exports ABA outward the cells. The newly synthesized ABA is then transported to the cells of acting site for ABA-responses by passive and/or active transport. The ABA importers and exporters can efficiently and directly deliver ABA to the acting site. However, part of the ABA is catabolic inactivated, which also plays a pivotal in regulating the intensity of ABA signal. PYR/PYL/RCAR receptors percept ABA signal intracellularly then combine with the negative regulators of ABA signal, PP2Cs/ABI1, to form a ternary complex. Thus, the negative regulator is inactivated whereas the downstream targets of PP2Cs, SnRK2s, are allowed to be activated by phosphorylation. The activation of SnRK2s will thus initiate an ABA response. In cell without ABA signal, the SnRK2s is inactivated by PP2Cs. http://www.thericejournal.com/

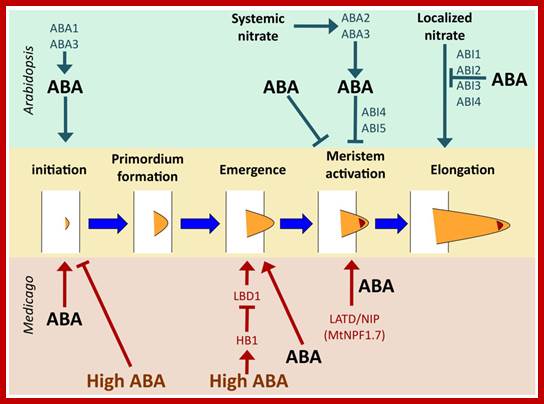

Regulation of lateral root development by ABA in Arabidopsis and Medicago. Key control points common to both species are initiation and meristem activation. Emergence from the primary root is an additional control point in Medicago. ABA stimulates initiation in both Arabidopsis and Medicago [55,56], but high concentrations of ABA inhibit it [56]. Salt stress inhibits lateral root emergence by stimulating ABA signaling, which induces expression of HB1, which in turn represses LBD1, required for emergence [56]. Lower levels of ABA stimulate lateral root emergence, but it is not known what functions downstream of ABA in this process [56]. Meristem activation is a key control point in both species, with systemic nitrate signaling via the classic ABA biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis and requiring ABI4 and ABI5, but not other ABA signaling genes [54]. ABA treatment in the absence of an environmental nitrate signal also regulates meristem activation, but does not require activity of any of the known ABA signaling genes [57]. In M. truncatula, this step requires activity of the MtLATD/NIP (MtNPF1.7) gene [17,58]. ABA treatment can bypass the requirement for MtLATD/NIP, inducing meristem activation in the absence of gene function [17]. Elongation of the lateral root subsequent to meristem activation is regulated by localized nitrate in Arabidopsis and can be repressed by ABA signaling; http://www.mdpi.com